Small patches of land provide relief from the heat, battle climate change, and provide some free fruit in Boston neighborhoods

By Ryan Krugman Inside Climate News October 3, 2025

“Edible forests” are popping up in Boston. Scattered across the city, once-empty lots have been overtaken by fruit trees and berry-filled bushes. Open to the public, they are forage-friendly pockets in the urban grid.

The rise of urban food forests in Boston can be attributed to the decade-long work of the nonprofit Boston Food Forest Coalition, also known as the BFFC. The group’s mission is to enhance low- and middle-income neighborhoods lacking green spaces. Over the past 10 years, the coalition has built more than a dozen food forests and caught the attention of city planners.

“When we first got started, we were dumpster diving for cardboard and other materials to help with soil remediation and beautification of abandoned lots,” said Orion Kriegman, BFFC’s founder and executive director.

The roots of the organization began at a trash-filled lot around the corner from Kriegman’s apartment in 2014 in Egleston Square, not far from the Franklin Park Zoo. With his neighbors joining in with shovels and spades, the crew spent hours digging up beer bottles, even a car that was half-buried in the soil. Within months, a small food forest filled with budding flowers and edible shrubs had sprouted.

Food forests differ from traditional community gardens by design and intent. While community gardens typically feature raised beds with caretakers seeding flowering annual plants, food forests center around perennial and indigenous fruit-bearing plants, mimicking the ecosystems of untamed woodlands in lots that range from 10 by 10 feet to the size of a city block.

When BFFC opened the Egleston Community Orchard, the city owned the land. That meant that at any point, the city could decide to develop it. So in 2015, Kriegman formally established BFFC as a community land trust that can acquire and hold land to ensure it remains permanently accessible for community use.

“We realized all our good work could be lost if we didn’t actually own the land,” Kriegman said.

From Mattapan to the North End, the nonprofit has now opened 13 food forests, with a goal of opening 30 by 2030 — a target shared by the city as part of its 2030 Climate Action Plan. The idea is simple: More trees and plants provide shade in areas lacking green space and suck carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas that drives global warming, from the atmosphere.

The carbon reductions from small patches of land may be small, but every tree or shrub makes a difference.

“Boston has ambitious climate goals, and the only way to achieve them is with robust efforts from diverse stakeholders,” said Elizabeth Jameson, director of climate policy and planning for Boston’s environment department.

The mayor’s housing office’s Grassroots Open Space Development Program and the Boston Planning and Development Agency provide city-owned parcels at reduced prices. The land the city distributes for grassroots initiatives is typically undesirable — due to size, location, or inaccessibility — for real estate or commercial development.

When a community identifies a site it wants transformed into a food forest, BFFC helps residents prepare a proposal. If approved — after a years-long process of community meetings — the city transfers the parcel into the group’s land trust, ensuring permanent community ownership.

Kriegman’s hope is that since food forests are now officially part of the city’s climate plan, the approval process will quicken, arguing that 30 food forests in a city of almost 700,000 people could be transformative.

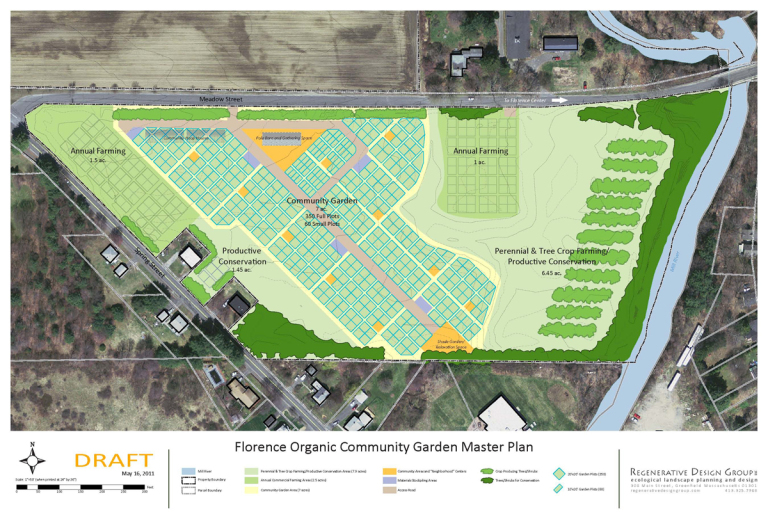

Boston Food Forest Coalition sites

There are 13 food forests across the city according to the coalition.

That’s because urban food forests can enhance biodiversity, offset pollution by filtering out pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter, and mitigate the urban heat island effect — the double whammy of heat trapped by asphalt and concrete. Vegetation and soils in food forests combat that heat. Trees and shrubs provide shade, plants release moisture, and soil naturally absorbs and stores heat more gradually.

A 2025 study by researchers in Taiwan examined a rooftop farm and other sites over three years and found lots with food forests were cooler on average by 2.2 degrees Celsius, about 4 degrees Fahrenheit, than surrounding areas.

The cooling effect of a small green space doesn’t extend far beyond the site itself — up to 100 meters — but expanding the number of food forests across a city could ease heat stress in neighborhoods that lack green spaces.

In Boston’s historically Black communities, there is a 20 percent disparity in accessible parklands and a 40 percent disparity in tree coverage compared with predominantly white neighborhoods, according to Boston’s Heat Resilience Plan. That means Black communities feel, on average, 7.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer during heat waves.

Beyond mitigating heat stress and pollution, food forests also provide fresh produce and a gathering hub.

More than 525 fruit trees and shrubs, with apples and cherries alongside lesser-known fruits such as pawpaws and serviceberries, can be found in Boston’s food forests. It’s all free with one caveat: take only what you need. Communities use the parks for picnics, birthday parties, movie nights, and yoga classes.

Neighborhood residents, called community stewardship teams, care for the land and collectively govern it through BFFC’s community land trust. Stewardship team leaders — 73 percent are women and 47 percent are people of color — ensure that community voices shape the coalition’s direction.

Every response is decided collectively — whether the problem is drought or an infestation of pests — a process that fosters trust-building and balances urgency with consensus.

That can be a challenge, too, said Kriegman. “Most people understand individual ownership, so it’s a constant challenge trying to educate people on what it means to own land together.”

The movement is growing despite headwinds from Washington. In May, the Environmental Protection Agency terminated $60 million for its Environmental Justice for New England Program. BFFC had been approved for a $250,000 grant, and it is unclear whether the organization will receive the money.

Still, momentum is not slowing. The nonprofit coalition has opened two food forests this year, and in August, it broke ground on a third site in Dorchester. It plans to open two or three new food forests in 2026.

“We’re moving faster than the city can keep up with because community demand and interest continue to grow,” Kriegman said.

This story is published in partnership with Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy, and the environment.

One of my most popular blogs was “

One of my most popular blogs was “